Researchers in Sweden have shown that electrical tuning of passive radiative cooling can be used to control the temperature of a material at ambient temperatures and air pressure.

Passive radiative cooling occurs when thermal energy leaves an object in the form of infrared radiation. The amount they emit depends on its ability to absorb infrared radiation. The better the material is at absorbing infrared heat, the better it is at emitting it.

Because of the atmosphere’s ability to transmit light in the infrared wavelength range, coldness in outer space (about -270°C) can be used to remove heat from objects on earth. An object can therefore be cooler than the ambient temperature.

“With the help of passive radiative cooling, the cold of outer space could be used to complement normal ACs and reduce energy consumption,” says Magnus Jonsson, professor and leader of the Organic Photonics and Nano-Optics group at Linköping University.

In recent years, science research has taken an increasing interest in this phenomenon. Now, according to researchers, the temperature of a device can be regulated by electrically tuning to a point where it emits heat through passive radiative cooling. The concept uses a conducting polymer to electrochemically tune the emissivity of the device.

“You can liken it to a thermostat,” says Debashree Banerjee, principal research engineer at Linköping University and principal author of the study. “Currently, we can adjust the temperature by 0.25°C. It may not sound like much, but the point is that we have shown that it is possible to carry out this tuning at room temperature and normal pressure.”

The team says there is now potential to further develop both materials and devices. In the long term, they envisage systems that can be laid on a roof, much like a solar cell, thus controlling the infrared thermal radiation from the house and cooling when needed. According to the researchers, this would require little energy consumption and cause minimal pollution.

In another study, the research group developed a thermoelectric device powered by the same principle of radiative cooling, also complemented by solar heating. This was based on generating a temperature difference between two cellulose materials, one of which contains carbon black to also absorb the heat of the sun.

The results have been published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science and reported on at the Linköping University website.

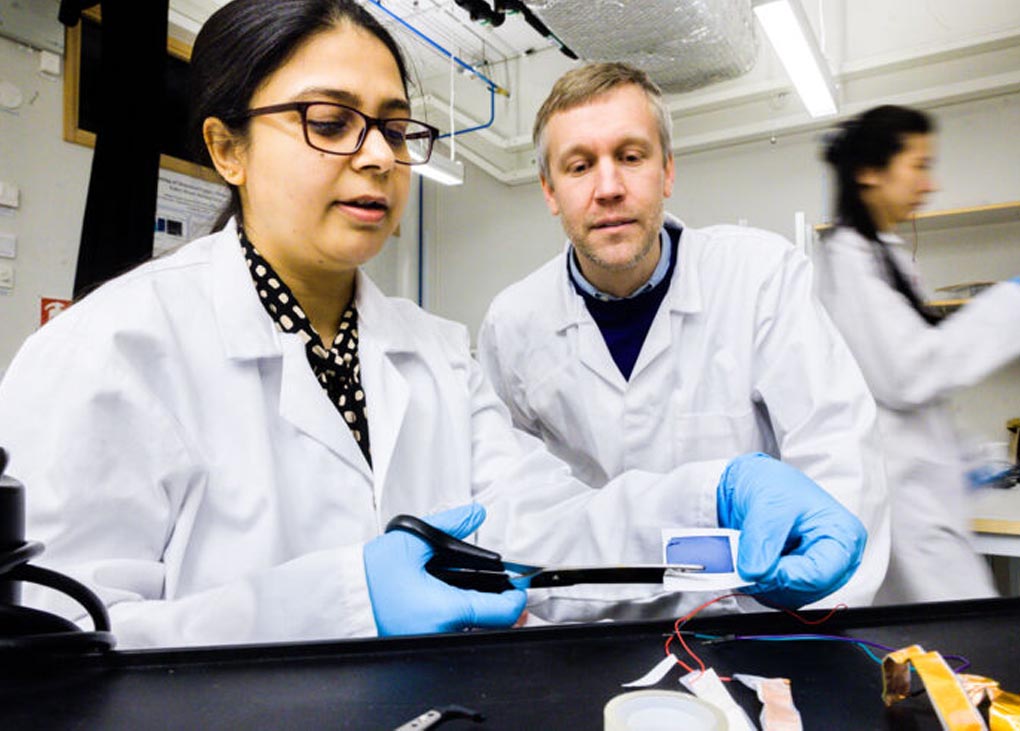

Image shows Debashree Banerjee, principal research engineer, Magnus Jonsson, professor, and Mingna Liao, PhD student. Photo by Thor Balkhed.

Louise Belfield

Louise Belfield

Leave a Reply