Scientists from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and Xerox PARC have released a study exploring the environmental impact of controlling humidity.

The research first appeared in the journal Joule, titled “Humidity’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions from air conditioning”.

While studies on air conditioners and greenhouse gases have been compiled before, this is the first in-depth study focusing on the impact of removing moisture from the air. The research has shown controlling humidity levels is responsible for approximately half of energy-related emissions.

NREL senior research engineer and co-author of the new study, Jason Woods, says it’s a challenging problem that people haven’t solved since air conditioners became commonplace more than a half-century ago.

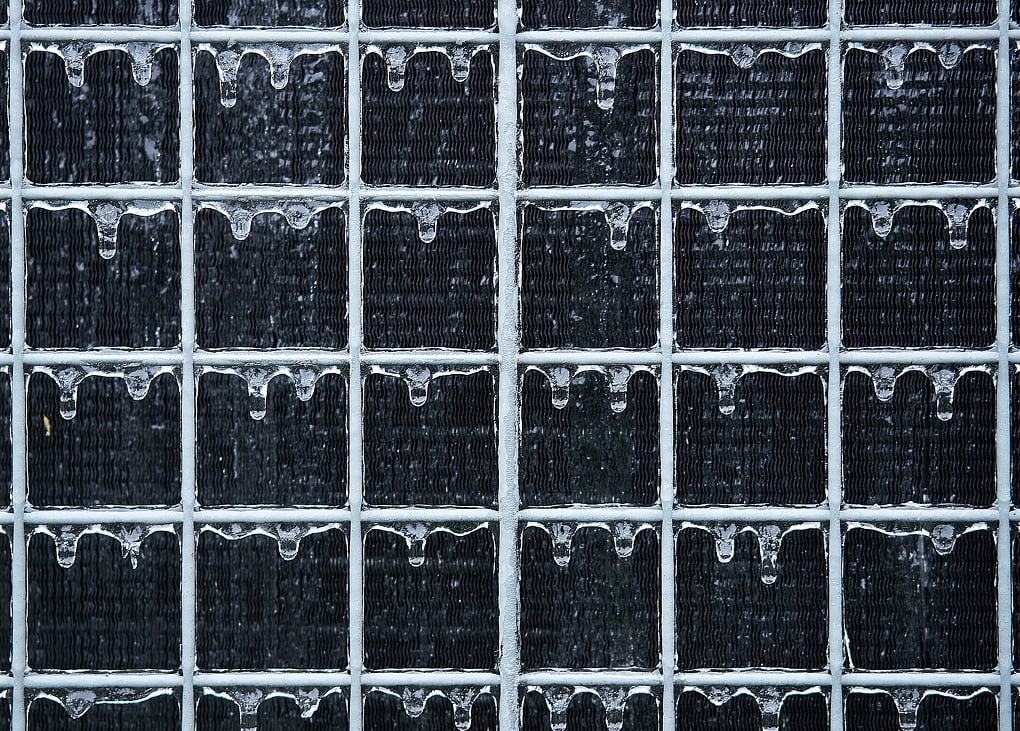

Even a small amount of humidity can make people feel uncomfortable and prompt them to turn their air conditioners on. Unfortunately, commercial air conditioners use a lot of electricity and can leak refrigerants that have a much greater global warming potential (GWP) than carbon dioxide.

The increasing need to cool the air is both a cause and an effect of climate change.

The study revealed air conditioning is responsible for the equivalent of 1,950 million tonnes of carbon dioxide released annually, which equates to 3.94 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Calculations showed 531 million tons comes from energy expended to control the temperature, and 599 million tons from removing humidity.

The researchers believe managing humidity levels contributes more to climate change than controlling temperature does – and the figure continues to rise as more people install air conditioners.

Woods says it’s a good and a bad thing.

“It’s good that more people can benefit from improved comfort, but it also means a lot more energy is used, and carbon emissions are increased,” he says.

The research was conducted using 27,000 simulations across the world for representative commercial and residential buildings. The team also predicted future energy use based on climate change predictions for global temperatures. The increase in humidity was predicted to have a larger impact on energy levels than temperature increases would.

The scientists concluded that new cooling technologies need to be considered, such as the use of liquid desiccant-based cooling cycles.

“To get a transformational change in efficiency, we need to look at different approaches without the limitations of the existing one,” says Woods.

The full study is available to read here.

Leave a Reply